Tamba Ware: A Timeless Tradition of Japanese Pottery

Japan is renowned for its traditional pottery regions, with

Japan is renowned for its traditional pottery regions, with

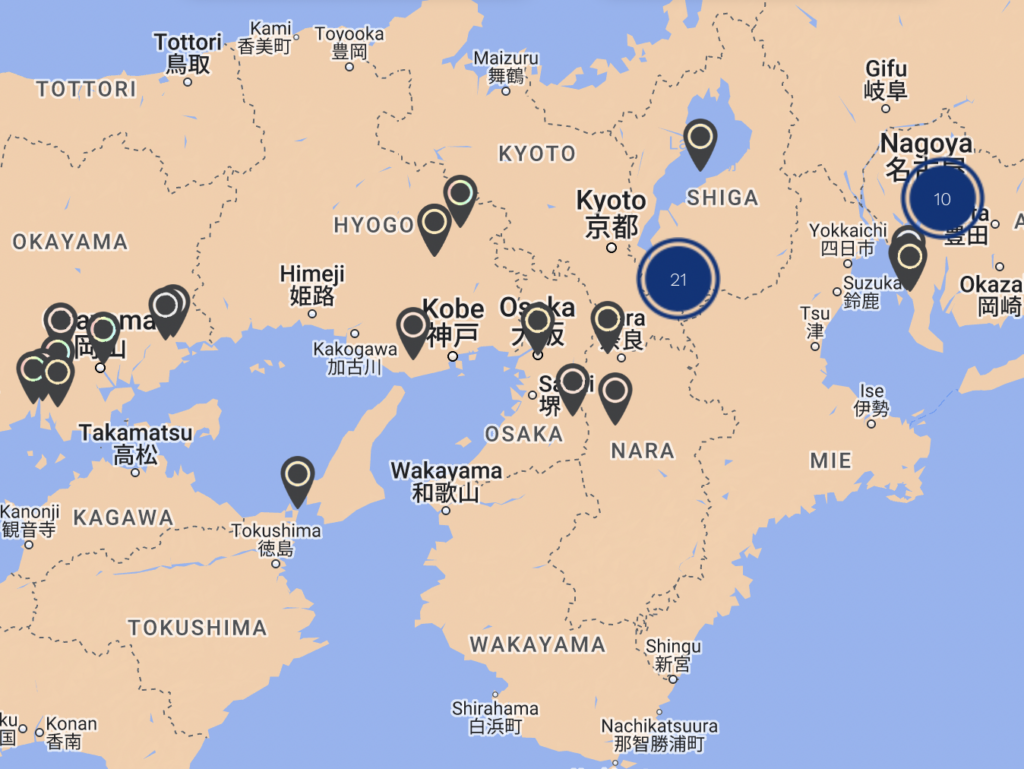

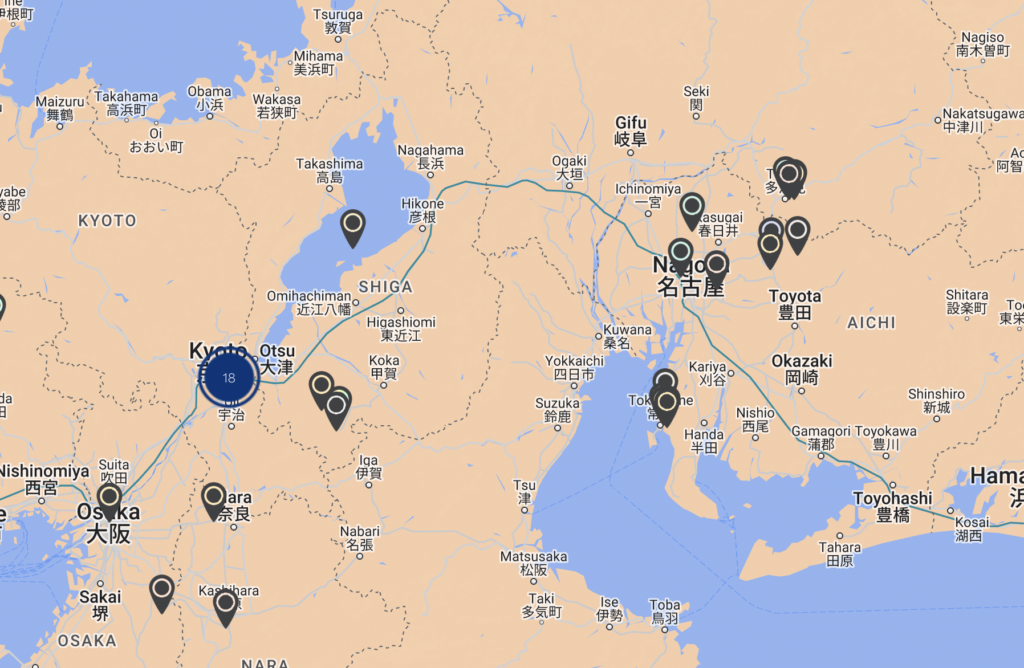

To see all the destinations listed in this guide and other ceramic sites worldwide, check out Ceramic World Destinations (CWD), MoCA/NY's interactive map listing over 4,000 destinations!

While Osaka may be renowned as 'Japan's Kitchen,' the city also holds great …

To see ceramic destinations in Shigaraki, Japan, and other sites worldwide, check out Ceramic World Destinations (CWD), MoCA/NY's interactive map listing over 4,000 destinations!

En Iwamura, a ceramic artist currently residing in Shigaraki, shares his experience working in the cultural…

Hitomi Shibata, a ceramic artist and author of the book Wild Clay, shares a personal essay about her time living, working, and making art in Shigaraki. This essay is part of our three-part feature on the cultural heritage site…

MoCA/NY asked three Japanese ceramic artists and academics to collaborate on our feature exploring the traditions, culture, and history of the significant cultural heritage site Shigaraki in Japan. Stay tuned for Hitomi Shibata's personal essay about her time working and…