Visions of Shigaraki, Japan

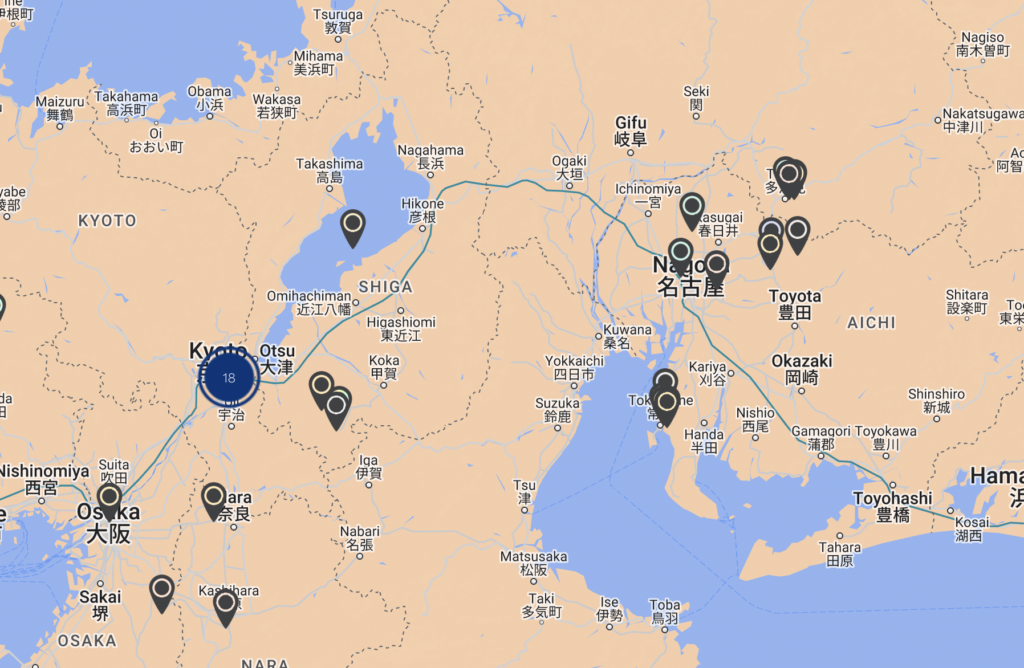

To see ceramic destinations in Shigaraki, Japan, and other sites worldwide, check out Ceramic World Destinations (CWD), MoCA/NY's interactive map listing over 4,000 destinations!

En Iwamura, a ceramic artist currently residing in Shigaraki, shares his experience working in the cultural

…

SHIGARAKI - Our Journey in Clay

Hitomi Shibata, a ceramic artist and author of the book Wild Clay, shares a personal essay about her time living, working, and making art in Shigaraki. This essay is part of our three-part feature on the cultural heritage site

…

GET TO KNOW: Shigaraki, Japan

MoCA/NY asked three Japanese ceramic artists and academics to collaborate on our feature exploring the traditions, culture, and history of the significant cultural heritage site Shigaraki in Japan. Stay tuned for Hitomi Shibata's personal essay about her time working and

…

Ilsy Jeon speaks with Hitomi and Takuro Shibata about their book Wild Clay co-authored by Matt Levy and published by Bloomsbury Publishing. The book not only provides an introduction and historical context to the material but also includes scientific breakdowns

…