In a Dutch underground bunker-turned-residency, a painter—Jonat Deelstra—is in the studio when his photographer friend arrives carrying several bags of wet clay. Like a child first encountering the soft, amorphous material, Deelstra’s sensorial curiosity takes over. Instinctively molding the unfamiliar clay, he conjures familiar forms—eggs—an implied image imprinted in his temporal lobe, evoking the ducks he often sees waddling across the nearby grounds.

He shapes solid, dense ellipses—a dozen or so—and calls a ceramic workshop to have them fired, only to have his request declined (the eggs aren’t hollow). In response, he carves out the interiors and uses the excess clay to form a figure perched atop each shell. A metaphor emerges: birth, and the inescapable cycle of lineage.

The other eggs are also hollowed, but the clay constructions grow increasingly abstract—eventually circling back to the literal, stirring reminiscences of coral reefs.

Four years of kismet, clay callings, and synapses in sync summon them into something more ambitious: a meditation on their role beyond metaphor. What if these vessels could house human remains? Could they serve as marine sanctuaries, fostering new life after death?

Funeral Home to the North Sea (2021) emerges as a speculative response to these questions—a visionary burial project that reimagines traditional funerary practices through ecological intervention. Deelstra envisions a series of ceramic urns designed to help restore Marine Protected Areas in the Dutch North Sea, which remain under-regulated and are routinely disrupted by bottom trawlers. “In the North Sea Agreement, which was signed in 2020,” Deelstra notes, “it was agreed that 15 percent of the Dutch North Sea floor should be protected by 2030. But today, we’re nowhere near that goal.”

Naturally, the personal undercurrents in Deelstra’s work are inescapable. His reflections on death arrive at a poignant moment—he loses his grandfather, an eccentric and intrepid man who lived on a houseboat floating along the canal. “My grandfather used to joke that we should make pancakes with his ashes and serve them at a party,” he recalls. His absurdist sense of humor—transforming morbidity into play—was a trait Deelstra clearly inherited. “So that stupid joke was actually quite important for my project,” Deelstra reflects. “To just think of death more broadly. Like, yeah, why don’t… why don’t we have some fun with it?”

His encounters with death rituals in India and Mexico—open-air cremations in vibrant Varanasi, the exuberance of Día de los Muertos—deepened his skepticism toward Western mourning customs, which, to him, lacked a certain sincerity. “The way we are approaching the ceremony of death,” he says of the solemnity and sterility of Western funerals, “it doesn't feel like my language.” His ceramic series of urns and coffins is, in part, an attempt to rewrite that language—with his grandfather’s remains as the first customer.

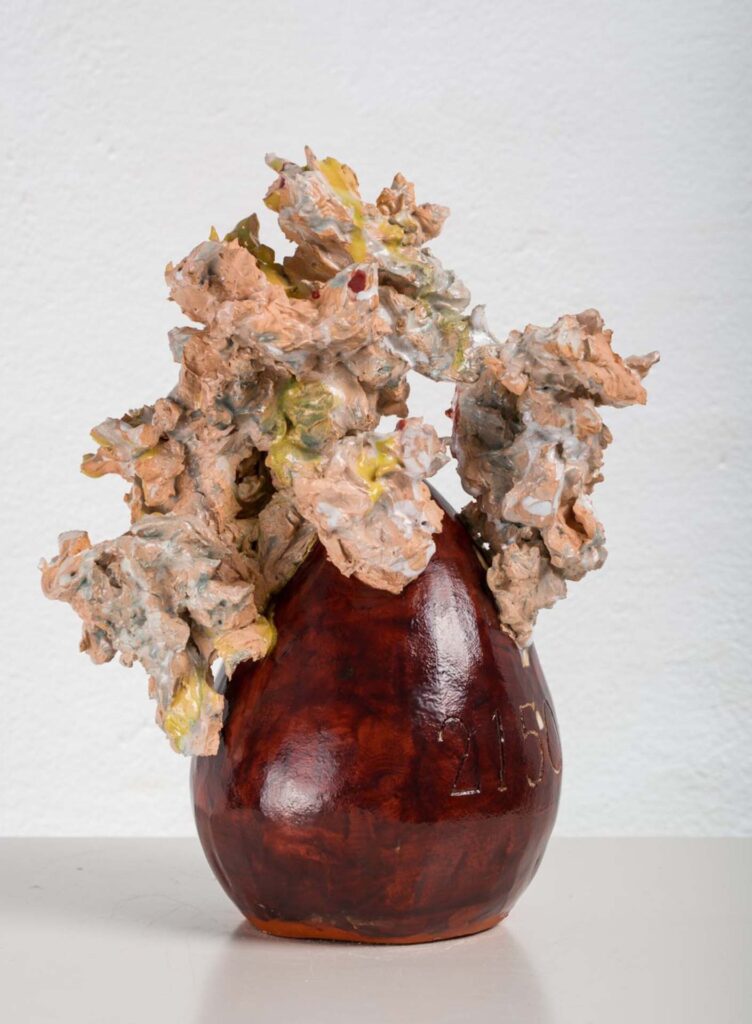

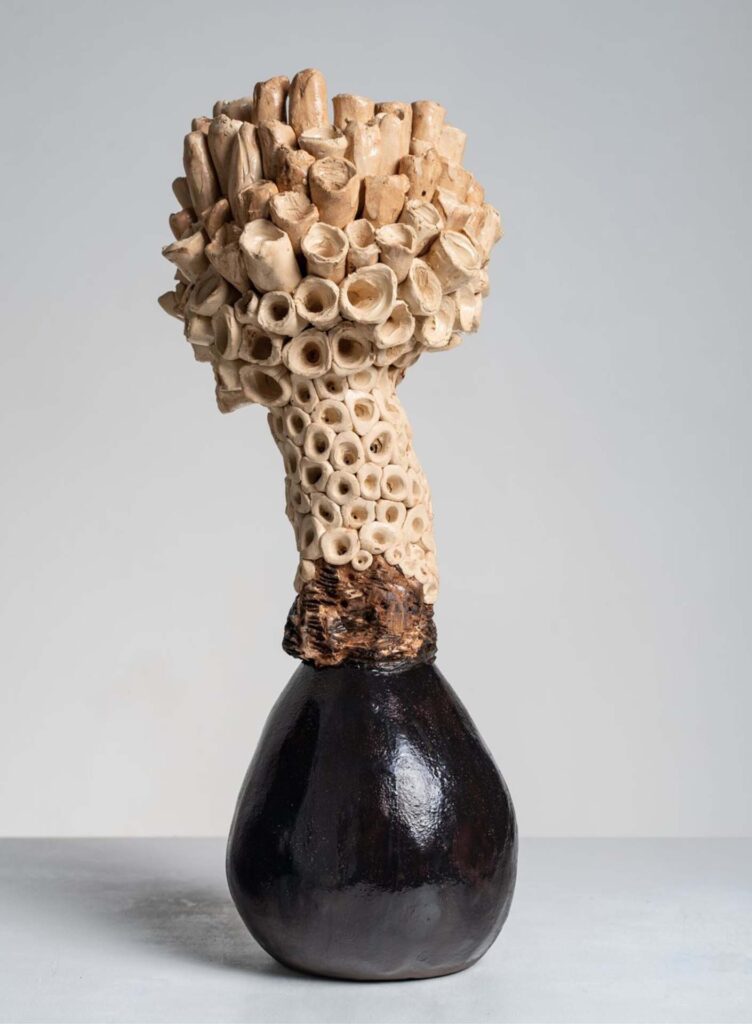

Ellipses—the same duck egg shapes—glazed in yellow, white, black, and muted, earthy tones, act as plinths: some rough and textured with squiggly lines, others smooth and luminous. Atop the eggs, corallite textures, calicular forms, incongruous cavities, and rugged, raised reliefs resemble oceanic life—clay imitations that may one day become homes for mollusks, seaweed, crabs, or starfish displaced by climate change and industrial fishing.

At first glance, these eggs do not appear provocative. They neither seem to challenge Western funerary traditions nor position themselves as environmental critiques. Yet they are a direct response to trawling—a method of dragging large nets through the water or along the seafloor to catch fish and crustaceans, often destroying habitats and sweeping up countless unintended victims. The coral-like copies become both an act of alarm and atonement—a graveyard and a potential habitat for anemones, sea lilies, sea urchins, and other marine life struggling to survive.

Deelstra’s project pushes beyond current initiatives around “green” and fungal burials, proposing instead the return of human bodies to the sea. Against the trophic, extractive, and anthropocentric impulses that have long shaped our relationship with the natural world, he offers an ecocentric vision—one in which humans live symbiotically with nature, offering not dominance but refuge, and perhaps even sustenance, to the very systems we’ve imperiled.

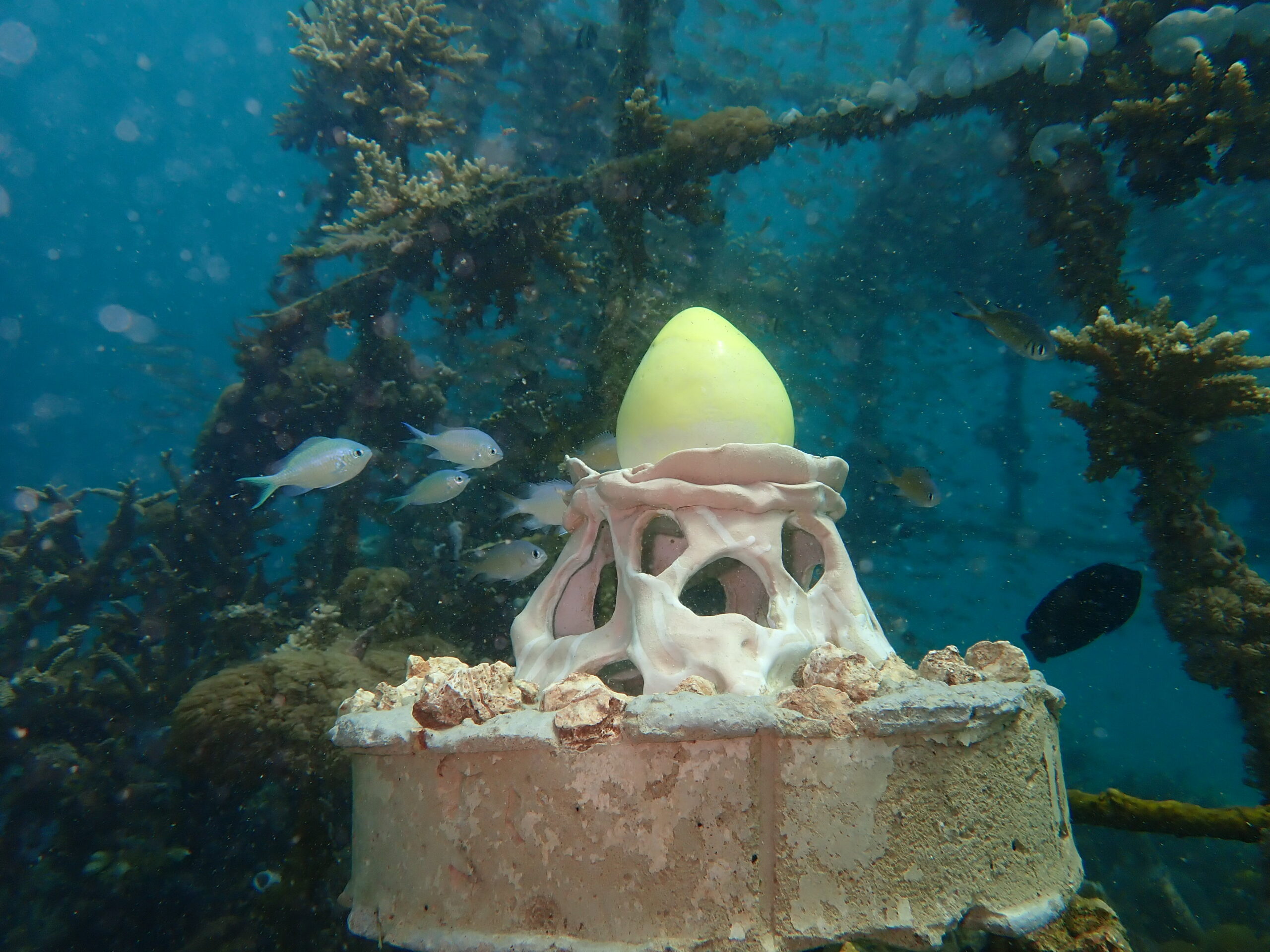

His process is as much scientific as it is artistic. He researches ceramic surfaces—testing different clays and glazes to determine their receptivity to oceanic life—and experiments with textures and shapes to observe which forms attract organisms. He even planted a prototype at the bottom of Grevelingenmeer, a saltwater lake in the south of the Netherlands with flora and fauna similar to the North Sea, and returns periodically to monitor its progress. During a recent inspection, he observed that seaweed and microorganisms favor specific glaze compositions, drawn to trace metals much as they are to submerged shipwrecks and oil rigs. Future iterations continue to unfold from these findings, with the aim of creating vessels that not only endure but actively contribute to the underwater world.

Alongside urns, he proposes creating coffins—shaped like giant oysters—designed to cradle a body and be submerged on the seafloor. Glazed in blue, beige, and white, each clay coffin becomes a resting place not only for the deceased but also for aquatic life.

Traditional burials consume too much land; cremations release excessive CO₂. So, how about composting our loved ones—or even dissolving them? The idea of becoming fertilizer for the ocean may sing like a swan song farewell to the physical realm, a divine return to the sea—or feel deeply unsettling. But concerns about toxins in human remains—whether cremated or corporeal—continue to raise ecological and ethical questions.

Beyond those lie cultural attachments, spiritual scaffolding, and the most bureaucratic obstacle of all: legal regulations. Yet he remains hopeful and enthusiastic, and pleasantly surprised by how many people are receptive—even excited—about his project. So much so, in fact, that he was invited to present the series as a solo booth with GoMulan Gallery at Ceramic Brussels 2025.

Remains stirred into pancake batter to feed the neighbors—offhand and absurd as the idea was—the quip lingered... His grandfather would later die tragically in a fire on his houseboat; in a surreal and ironic twist, his body was cremated on the water. As an homage, his remains became the first clay egg to be laid to rest off the coast of Kenya, in a coral reef restoration zone.

SQUATTER OF THE NORTH SEA

In this short film, artist Jonat Deelstra invites viewers beneath the waves to explore Funeral Home to the North Sea—a visionary project that merges ceramics, ecology, and mortality. Shot by filmmakers Peter Balm and Pim Havinga, the video traces Deelstra’s journey from a spontaneous clay experiment to an ambitious plan for underwater cemeteries that double as marine sanctuaries. Through interviews, studio footage, and submerged prototypes, the film reveals how art can serve as both a vessel for mourning and a catalyst for environmental restoration.

Visit Jonat Deelstra's website to learn more: CLICK HERE