In the foothills of Saja Mountain, in South Korea’s Jangheung, Jeollanam-do, an unassuming slope conceals one of the country’s most singular art spaces: a one-hundred-meter grotto, dug entirely by hand, its 1,650 square meters winding through a labyrinth of chambers and tunnels. The walls bloom with roots, skulls, celestial beings, and Buddhas; shallow alcoves cradle candles that bathe the space in a warm, meditative glow. This is the life’s work of Dae-chul Kang—once hailed as a rising star of Korean sculpture—who vanished from public view for nearly two decades before re-emerging with an “underground museum.”

Since the 1970s, Kang has moved fluidly between wood, stone, bronze, resin, and clay. Recognition came swiftly: the Minister of Culture Award and the Grand Prize at the inaugural JoongAng Art Competition in 1979, followed by major commissions, including a memorial to the revered Buddhist master Seongcheol. By the turn of the millennium, his career spanned more than a hundred group shows, a dozen solo exhibitions, and the direction of international sculpture symposiums.

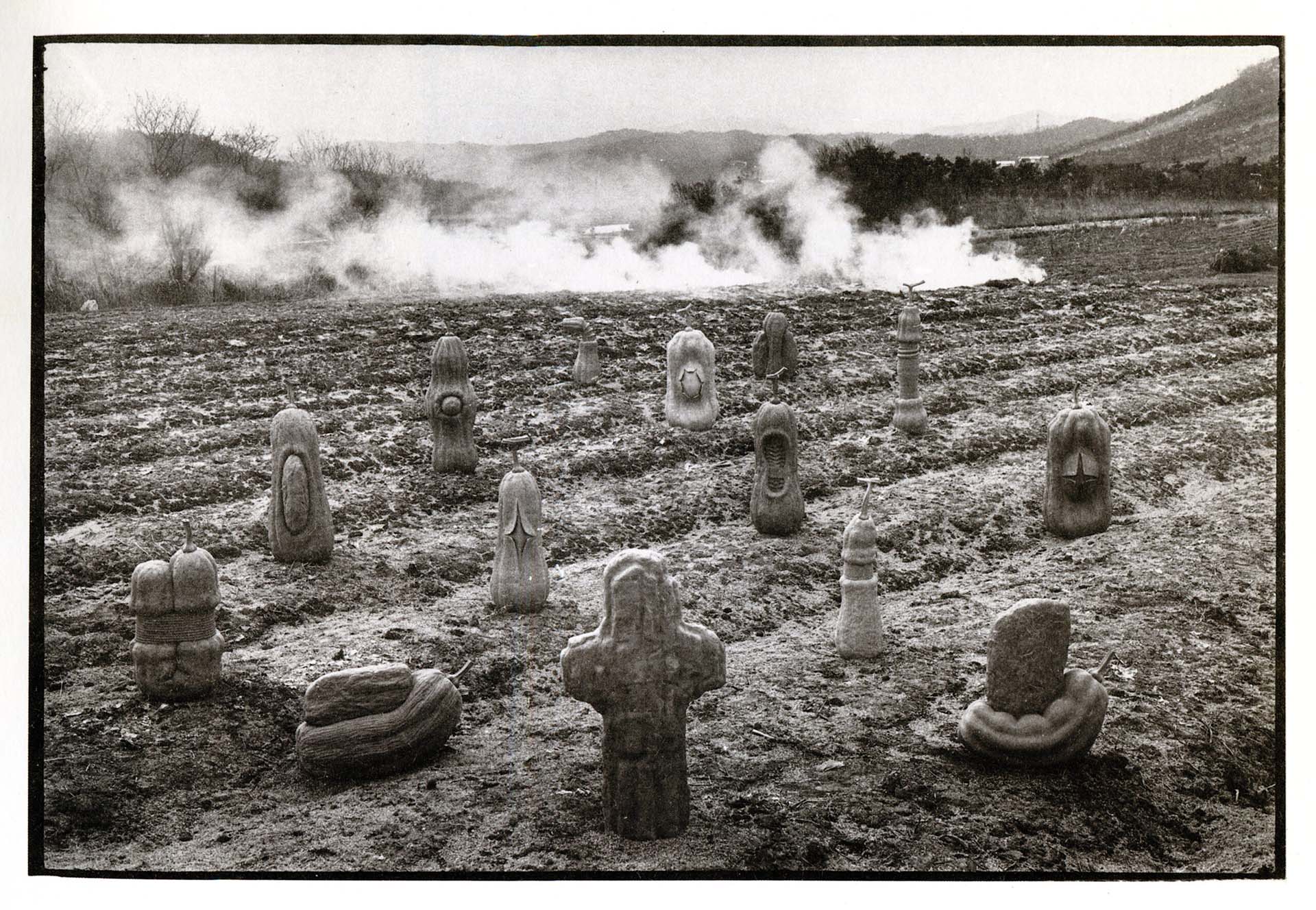

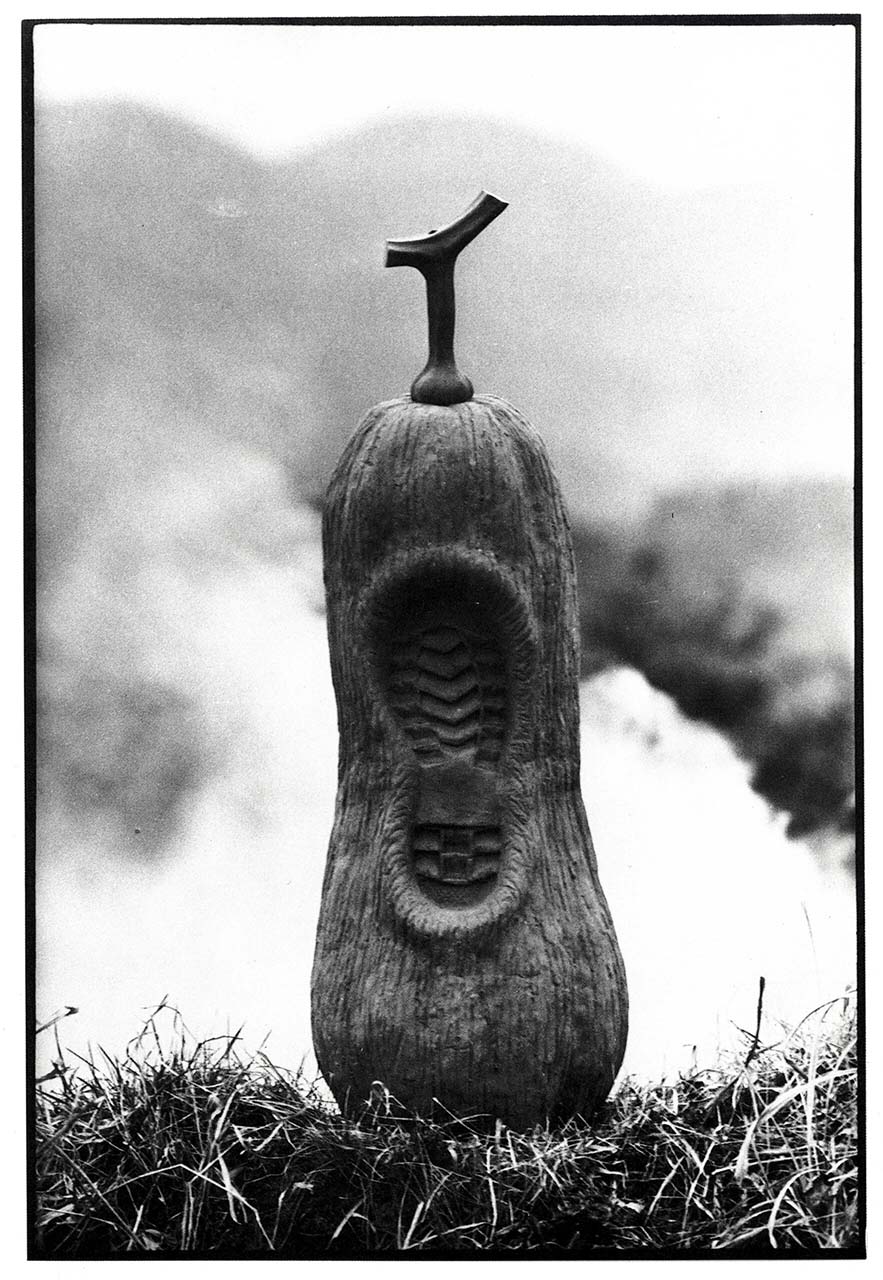

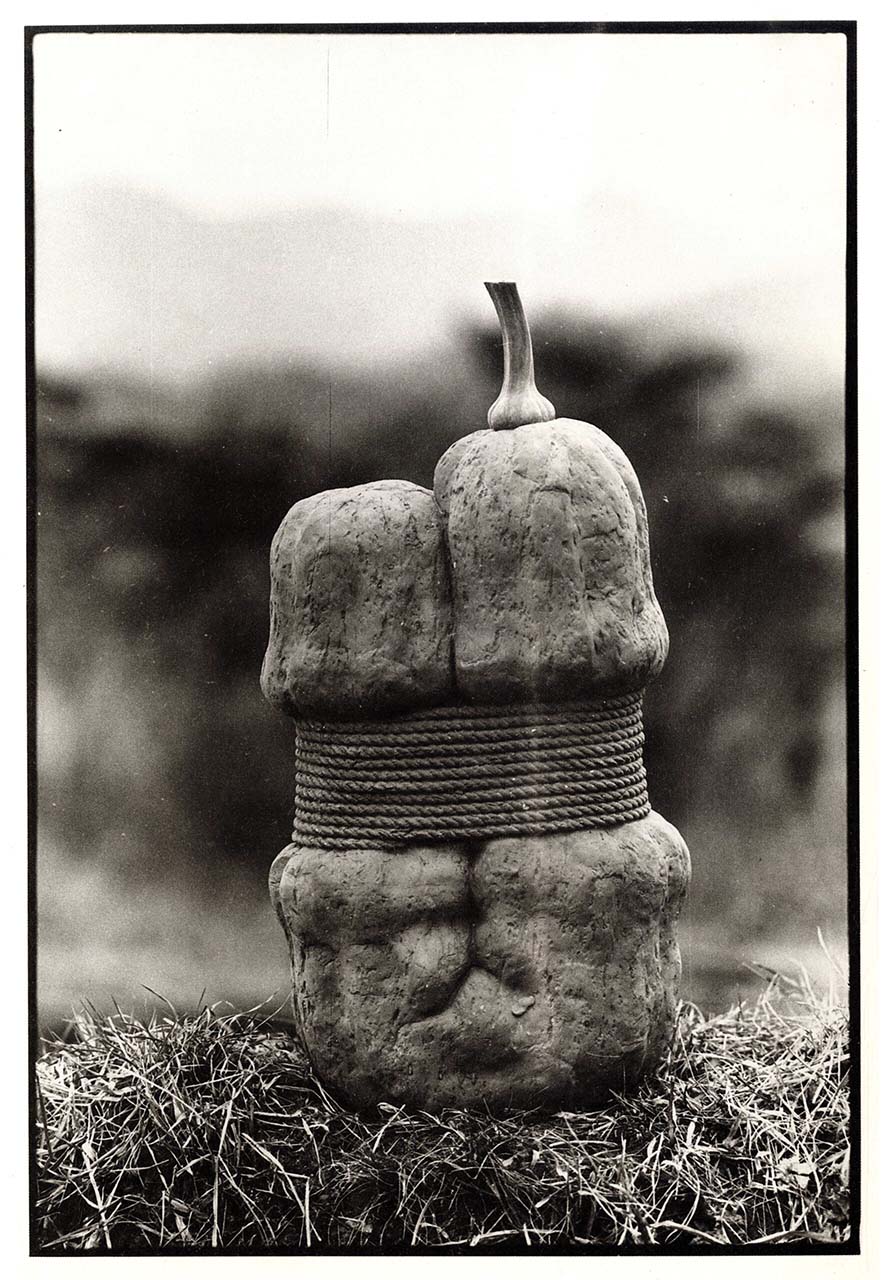

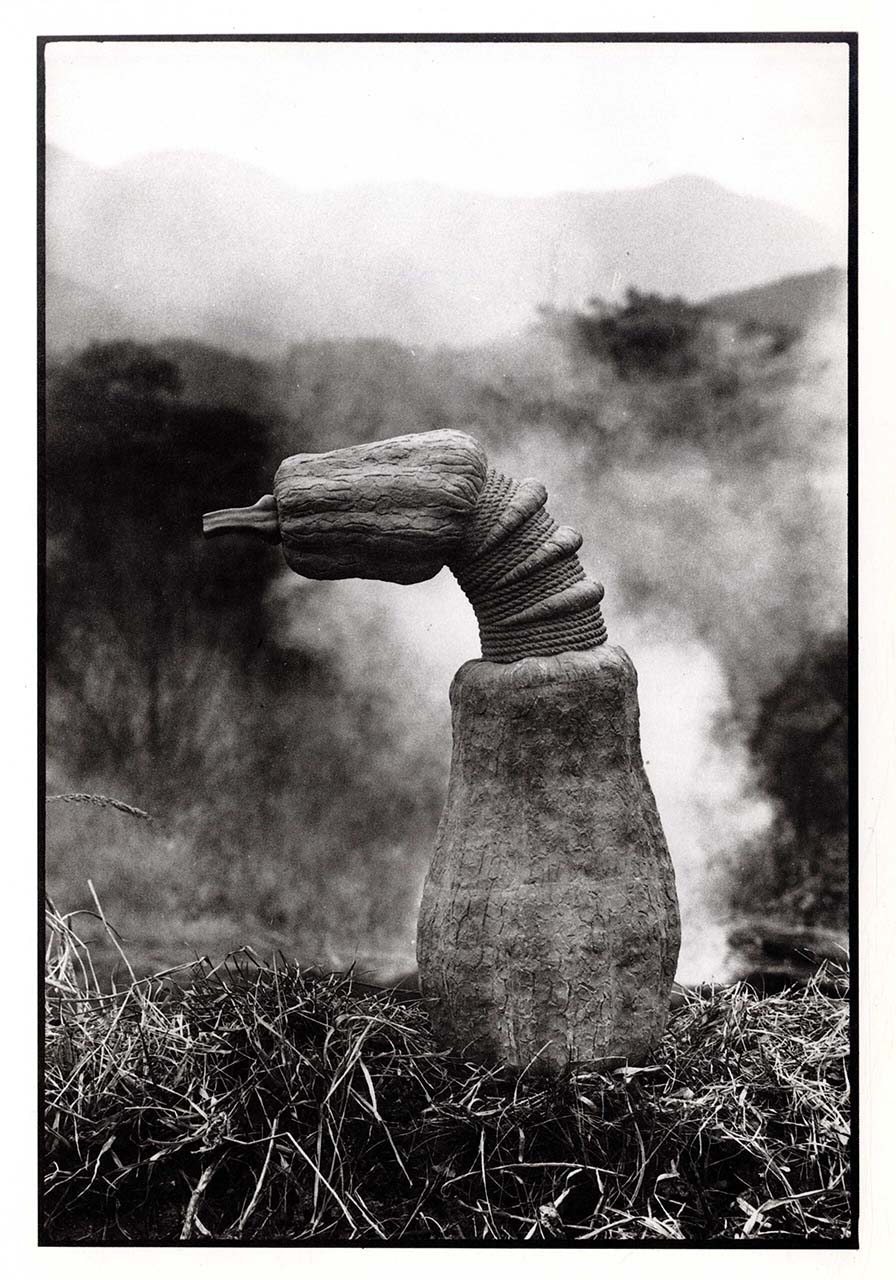

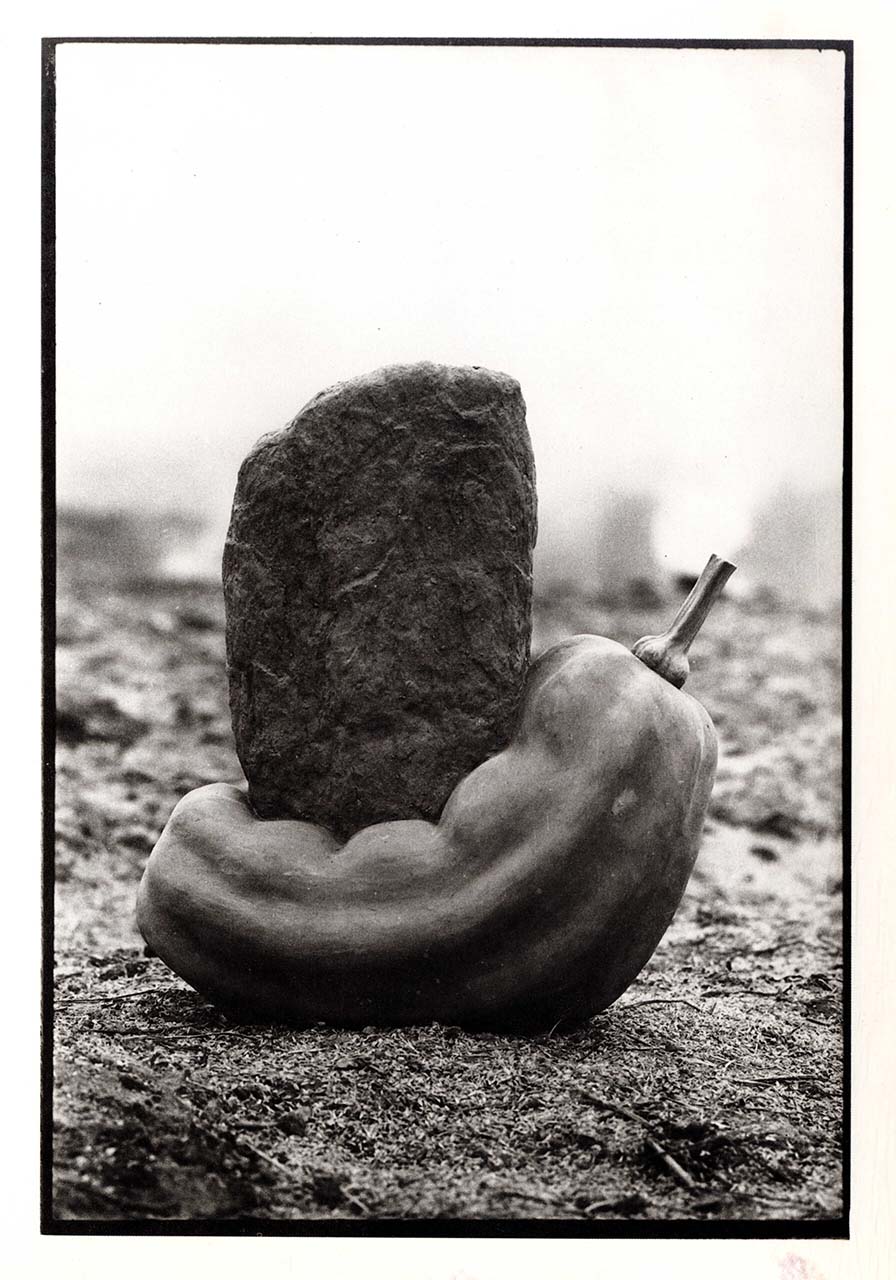

His terracotta series Pumpkins of K’s Farm (1983) marked a turn toward sharper political expression. Molded in clay and shown bound, crushed, or bearing the tread of military boots, the pumpkins formed a coded elegy for the victims of the 1980 Gwangju Democratization Movement—a pro-democracy uprising remembered as one of the most defining and devastating moments in South Korea’s struggle to end authoritarian rule. While official accounts reported around 200 dead, other estimates place the toll closer to 2,000. In their battered forms, Kang captured not only the violence of the state but the enduring will of a people who, even under the heaviest weight, refused to surrender their form.

In the years that followed, the urgency of Kang’s political commentary gave way to a more introspective, spiritual vision. By the 1990s, his work had turned inward. Titles such as Seeker, From Ignorance, Koan, and Nirvana reflected a deepening engagement with Buddhist philosophy and his involvement in the Panvital Transcendentalism movement, which sought to restore the sacred value of life. Raised in a devout Christian household, Kang began merging Christ and Buddha into single forms—sculptural meditations on the shared truths he saw in both faiths and on his own passage from one to the other.

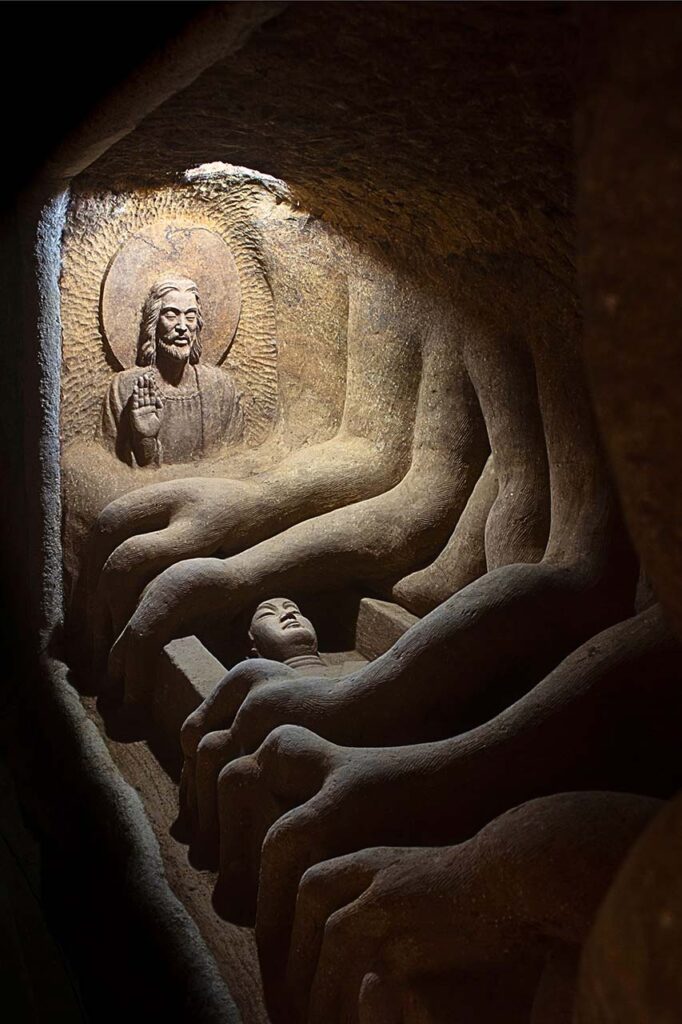

Then, around 2002, Kang withdrew from public view. He settled on the slopes of Saja Mountain, in a hermitage once occupied by a monk. What began as a modest plan for a tea room changed course when he discovered the soil—a dense blend of decomposed granite and loess (wind-blown powdery clay)—was perfect for carving. “It was destiny,” he says. With a pickaxe in hand, he began to dig. Every day, in solitude, from dawn to dusk, the hours dissolved into days, and the days into years, until ten had passed. Out of the mountain’s body, chambers and tunnels emerged: a reclining Jesus facing the Maitreya Buddha; reliefs of the Five Aggregates; skeletons locked in contemplation; roots knotted like neurons; a fetus cupped between brain hemispheres. For Kang, the work was no longer separate from the search. The artist’s path and the seeker’s path had become one.

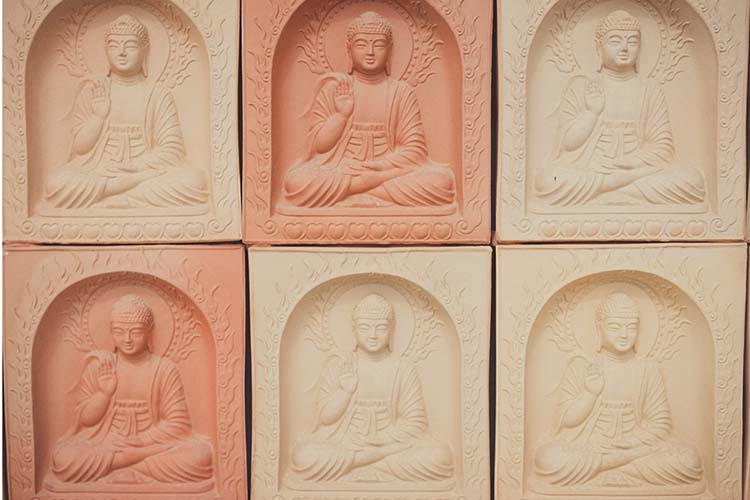

After ten years of solitary excavation, the Sculpture Cave now spans seven grottoes, each with its own spiritual focus. “Digging and carving was a form of prayer,” Kang says. That same convergence of art and faith shaped his public work—most notably, Korea’s first large-scale cave-style memorial hall for Master Seongcheol in Sancheong, completed in 2015. The three-story, 765-square-meter sanctuary is lined with thousands of ceramic Buddhas and crowned with celadon reliefs of Flying Celestial Beings. Kang not only conceived the building’s architecture but also created the sculptural elements, from the exterior walls to the innermost alcoves, working in ceramics, stone, bronze, and synthetic resin.

Now in his late seventies, Kang has published Kang Dae-chul’s Sculpture Cave and the poetry-and-art collection Suddenly, One Day. The cave, still unfinished, is envisioned as a space for practice and dialogue, open to those “meant to join” him. Most days, however, he remains at work—digging, carving, meditating. In the dim glow of his grottoes, surrounded by clay and silence, Kang carves not only into the mountain’s flesh, but into the unseen contours of his own truth.

IN THE STUDIO WITH Dae-chul Kang

Explore the hidden world of The Sculpture Cave in this evocative video portrait of Kang’s underground museum. Through candid reflections and intimate footage, the artist reveals how a modest plan for a tea room grew into a sacred labyrinth, carved entirely by hand into the mountain. With philosophical insight, Kang reflects on how each relief, form, and figure became both a spiritual offering and a journey inward—where digging is prayer, and the mountain itself becomes canvas, contemplation, and creation.

Interested in purchasing Dae-chul Kang’s books? Visit the links for Kang Dae-chul’s Sculpture Caveand the poetry-and-art collection Suddenly, One Day.

MoCA/NY extends heartfelt thanks to Yoewool Kang, daughter of the artist, for her generous collaboration on this feature.

Yoewool Kang is a lecturer in East Asian Philosophy and Aesthetics at Yonsei University, Seoul. She holds a BA and PhD in Philosophy from Yonsei University and an MSt in the History of Art from Oxford University. Her experience includes work with the World Ceramic Biennale, Busan Biennale, and Gwangju Biennale.

MoCA/NY delivers fresh stories, bold ideas, and inspiring voices from the world of contemporary and traditional ceramics—straight to your inbox.

Subscribe today to keep the momentum going!