Visit Pewabic Pottery House and explore other manufacturers, studios, and ceramic destinations in the US through Ceramic World Destinations (CWD), MoCA/NY’s interactive map featuring over 4,000 ceramic sites worldwide.

In the early 20th century, Detroit was a city in motion. Smoke and steel defined the skyline, and the hum of industry heralded the rise of the automobile and the promise of modernity. Amid this rapid industrialization, Mary Chase Perry Stratton and Horace Caulkins founded Pewabic Pottery in 1903—a small studio devoted to traditional, handcrafted ceramic methods at a time when mechanization dominated American life. The name “Pewabic” itself recalls Michigan’s northern landscape, evoking a copper mining region that shaped Stratton’s early life and sensibilities.

From its earliest days, Pewabic stood as a counterpoint to the era’s obsession with speed, efficiency, and mass production: a place where careful attention, skill, and material intelligence mattered.

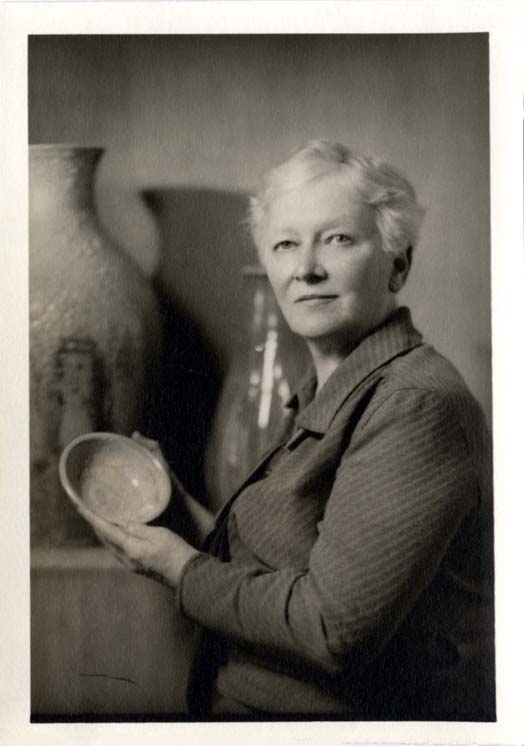

Stratton, a woman working long before women could vote, brought a bold vision to Detroit. She was fascinated by historic ceramic traditions, particularly the luminous luster of 12th-century Syrian wares. She was introduced to these by her friend and patron Charles Lang Freer—whose collection of Asian art would later become part of the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art—and drew deep inspiration from their ancient surfaces as she developed Pewabic’s signature iridescent glazes. These glazes were not simply decorative; they carried layers of meaning, linking Detroit craft to centuries-old global traditions and demonstrating that thoughtful, handcrafted work could command attention even in a world dominated by industry.

Stratton’s studio was never intended as a novelty—it was a working pottery with a serious focus on education and craft.

From the beginning, Pewabic employed skilled artisans, many of whom immigrated to the United States to join the studio. They brought centuries of European ceramic tradition with them, and some had heard of Pewabic specifically because it preserved old methods of making pottery and tile.

Their expertise in wheel throwing, tile pressing, and kiln firing was essential to bringing Stratton’s vision to life. Men and women worked side by side, blending skill, innovation, and traditional techniques. Apprentices and students learned by doing, ensuring that knowledge would be passed on even as the studio evolved.

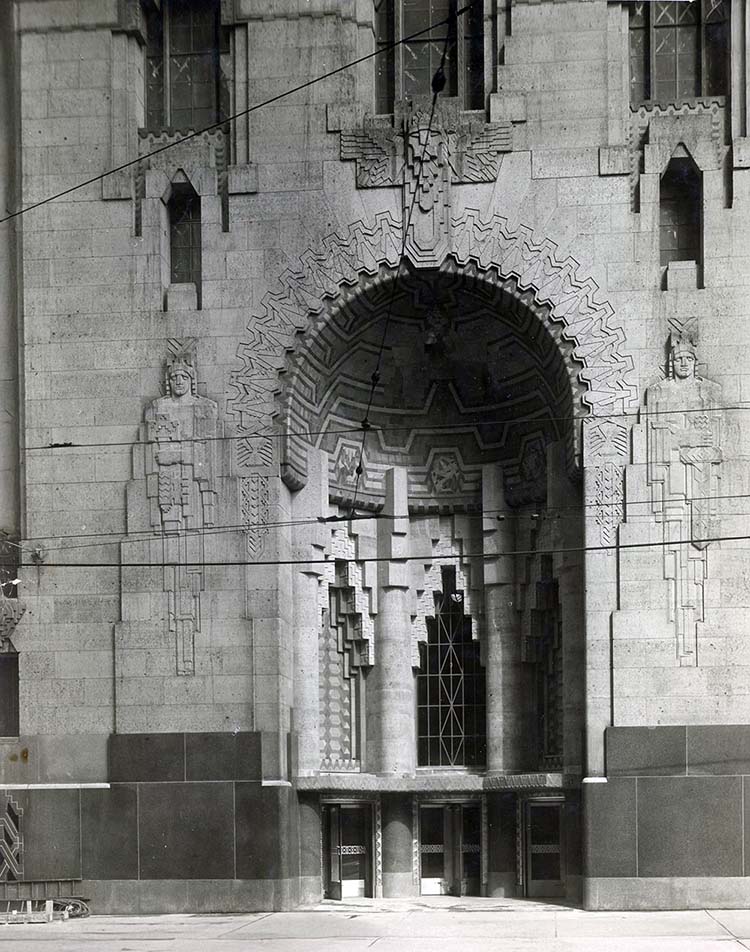

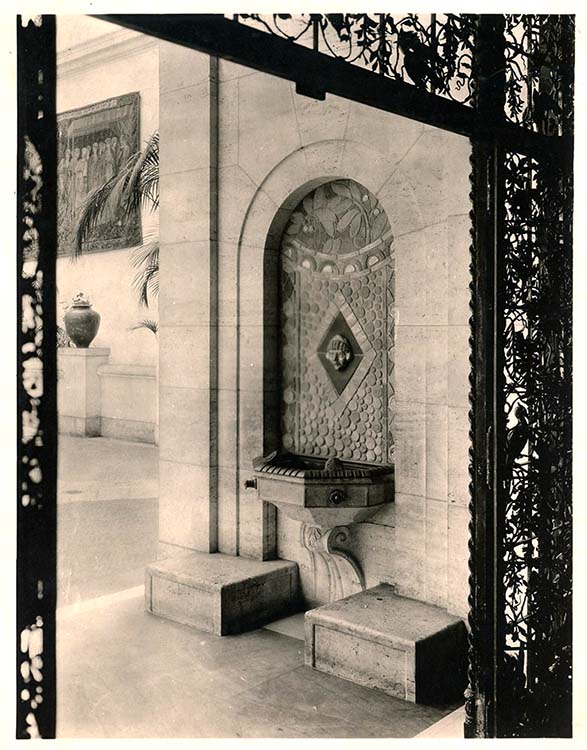

At the heart of Pewabic Pottery lies tile production, and it is through tile that Pewabic most visibly shaped Detroit. Stratton cultivated close relationships with architects, educators, and civic leaders, producing tiles for schools, theaters, churches, and public buildings. Pewabic tiles were more than adornment; they contributed to the architectural identity of the city, integrating handcrafted surfaces into walls, floors, and decorative details.

Detroit’s own geological resources supported this work–early Pewabic operations often incorporated local clay and terracotta, materials that could be found throughout the city and proved especially useful for large-scale architectural installations. Iconic locations such as the Guardian Building, the Detroit Institute of Arts, and the Detroit Public Library display Pewabic tiles in ways that highlight both craftsmanship and artistry, creating spaces where architecture and ceramic art are inseparable. The studio’s work was both influenced by the city’s architectural ambitions and influential upon them, embedding Pewabic’s craft into Detroit’s cultural landscape.

Despite its anti-industrial roots, Pewabic found unexpected harmony with Detroit’s industrial rise. The studio supplied tiles to automotive manufacturing facilities, industrial buildings, and the homes of some of the city’s most prominent business leaders. These collaborations demonstrate the adaptability of Pewabic’s craft: handmade tiles could coexist with mechanized production, offering a human touch and aesthetic consideration that machines alone could not replicate.

Pewabic has always been flexible, viewing the studio as a living entity rather than a static model. This perspective has allowed the pottery to pivot over decades, responding not only to changes in materials and artistic trends but also to the dramatic swings of Detroit’s local economy. Periods of growth fueled major commissions and expansions, while times of contraction forced the studio to rethink its scale, staffing, and operations. These economic tides—automotive booms, industrial decline, population shifts, and now renewed investment in the city—have all left their mark on Pewabic’s daily practice. Yet through each turn, the studio has endured as more than a museum piece: it remains an active, creative force, continually adapting to the circumstances of its time while preserving the essence of its craft.

More than a century later, Pewabic’s glazes remain central to its identity. Stratton experimented with layering glaze recipes and firing methods, achieving surfaces that shimmered with depth, color, and light. Iridescence became a hallmark of the studio, setting Pewabic apart on the national stage. While today’s glazes continue to draw inspiration from Stratton’s original recipes, many of those historic formulas contained materials that no longer meet modern health and safety standards. Combined with the changing availability of raw materials, this has meant that Pewabic regularly reformulates glaze recipes, always balancing respect for tradition with the realities of contemporary practice. A ceramic materials engineer is part of the studio’s team, supporting glaze development, clay body formulation, and ongoing experimentation to ensure both safety and artistic integrity. In every piece—whether tile, vessel, or sculptural form—the surface reflects this dialogue between past and present, precision and innovation, material and maker.

Education and mentorship have always been central to Pewabic’s mission. From early apprentices to today’s classes and workshops, the studio fosters skill-sharing across generations. Contemporary programming includes both onsite and offsite opportunities, from workshops at the historic studio to partnerships that bring ceramics directly into Detroit schools through collaborations with Detroit Public Schools Community District (DPSCD). These programs carry forward Stratton’s philosophy of learning by doing, ensuring that students, apprentices, and community participants engage with the hands-on processes of clay and glazing.

The culture of collaboration, mentorship, and experiential learning keeps ceramic knowledge alive and accessible. Pewabic does not merely preserve history–it continues it, maintaining a dialogue between past techniques and contemporary practice, allowing the studio to remain vital through Detroit’s cycles of growth, change, and renewal.

Civic engagement has long been a cornerstone of Pewabic’s work. Early commissions from architects and civic leaders not only sustained the studio financially but also embedded its craftsmanship into Detroit’s public spaces. That tradition continues today: Pewabic tiles are featured in major contemporary projects such as the QLine stations and Little Caesars Arena, bringing handcrafted ceramics into the city’s evolving infrastructure. The studio’s independent artist gallery also remains a key part of its mission – a space dedicated to showcasing and supporting ceramic artists from across the country. This commitment to artist-driven practice extends Pewabic’s legacy of creative exchange, reflecting a continuity that reaches back to Stratton’s time and forward to the next generation of makers.

In every tile laid and glaze fired, the studio upholds a commitment to skill, collaboration, and the belief that art can shape the lived environment. Over more than a hundred years, Pewabic has maintained a rare combination of continuity and flexibility. It is grounded in tradition yet responsive to change; it honors centuries-old techniques while engaging contemporary materials, equipment, spaces, and audiences. Today, the studio is home to a collective of artists rather than a single artistic voice—continuing the collaborative spirit first envisioned by founders Mary Chase Perry Stratton and Horace Caulkins. Its influence is tangible in Detroit’s architectural landmarks, civic spaces, and private homes, and its reach is equally cultural, inspiring artists, educators, and designers nationwide.

Pewabic Pottery endures not as a relic of the past, but as a living, breathing practice—a studio where history, craft, and civic life continue to meet in clay.

Annie Dennis is an artist and educator in Detroit. She received a BFA Ceramics from Western Michigan University and MFA Ceramics from Cranbrook Academy of Art. As Education Director and Archivist at Pewabic Pottery, Annie is working to share the history of one of the nation’s oldest continuously operating potteries. Contact: [email protected] | Pewabic Pottery Website