Japan is renowned for its traditional pottery regions, with six notable areas known as the Six Ancient Kilns of Japan that have stood the test of time. Among them, Tamba—also called Tachikui or Tamba-Tachikui—stands out and has continued to evolve over a millennium. Recognized as an intangible cultural property of Japan, Tamba ware has always been deeply intertwined with daily life, adapting to reflect changing lifestyles. In recent years, contemporary pieces like flower vases and flat plates have become more popular, seamlessly fitting into modern living.

Crafted in the Tachikui area for around 800 years, Tamba ware initially focused on practical items such as jars, urns for water and grain storage, and cooking mortars. Today, about 60 kilns continue this legacy, producing a wide array of items that supply the needs of everyday life. While often linked with simple red clay jars and urns, Tamba ware actually encompasses all ceramics made in Tamba and has no fixed style.

The tranquil rural landscape around Tachikui provides a picturesque backdrop for Tamba ware's creation. Despite its peaceful village charm, it's only about an hour's drive from major Kansai cities like Osaka, Kyoto, and Kobe, and about two hours by train. The area near Sasayama Castle, a key spot for Tamba Sasayama tourism, is about a 20-minute drive away, making it a popular destination for travelers using taxis or rental cars.

The diversity and adaptability of Tamba ware are partly due to the unique distribution methods of Tamba Sasayama craftsmen. Unlike many other pottery regions where middlemen handled distribution, The craftsmen often delivered their creations directly to shops in cities like Osaka and Kyoto. This direct interaction kept them in tune with urban trends, allowing them to create pieces that resonate with people and meet their contemporary need.

The tradition of passing down Tamba ware through generations is deeply rooted in this ancient craft. Masters often hand over the names of their houses (studios) and the knowledge of techniques, kilns, and clay recipes to their children, usually the eldest sons. If a master has multiple children, the second child is expected to establish a new house and adopt a new name.

While there are occasionally newcomers from outside the Tamba pottery area, such instances are rare. This rarity is likely due to the long-standing customs of this old village, which can be challenging for outsiders to adapt to.

The historical timeline of Tamba-ware is rich and fascinating. Tamba ware’s roots stretch back to the end of the Heian era (794-1185), based on local production of Sueki pottery (unglazed ceramics). It also absorbed techniques from Tokoname ware and Atsumi ware, produced in the Tokai region. During the Middle Ages, Tamba ware primarily consisted of pots and mortars. The bright brown surface of Tamba ware transforms in high kiln temperatures, becoming a beautiful yellow-green natural glaze.

In the Edo period (1603-1868), sake bottles and pots slip-painted with “akadobe,” a material rich in iron, became popular for their striking red color. The period saw the introduction of the noborigama and keri rokuro, revolutionizing production and diversifying products, leading to innovations in glazes and techniques. Tamba tea pots and mortars were highly sought after and exported to Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo.

The Kamaza pottery association initially controlled the market, later taken over by the Sasayama clan, spreading Tamba ware across Japan. By the Meiji to early Showa eras, transportation expanded distribution, leading to the production of major items like sake and soy sauce bottles, and flower pots. Later, chestnut-colored “Kurikawa-glaze” and white slip-painted, multicolored overglaze items emerged, adding to the area's diverse ceramic techniques. Tamba ware, along with the other five ancient kiln sites, was recognized as a Japan Heritage site in 2017.

One of Tamba ware's most distinctive features is its long climbing kilns, built along hillsides. The oldest Tamba ware kiln, established in 1895, is still operational today. It has been registered as an Important Tangible Folk Cultural Property of Hyogo Prefecture, and its construction technique has been designated as an “Intangible cultural asset of which records should be created” by the Japanese government. By 2014, the kiln had aged significantly, necessitating two years of restoration.

This effort, led by the Tamba Tachikui Ceramic Ware Co-Operative with support from citizens and volunteers, brought the kiln back to life. It was fired again in the autumn of 2015. Since 2016, the kiln has been used annually to fire pieces created by children, university students, volunteers, and other local artists. Starting in 2018, the kiln firing became part of the Spring Festival events, continuing the tradition and cultural heritage of Tamba ware.

Located in the "Tamba Pottery Old Village," the Museum of Ceramic Art, Hyogo is a cornerstone of the region’s cultural heritage. Opened in 2005, the museum promotes ceramic and porcelain culture, fosters international exchange, and supports educational initiatives. It cultivates future artists, collaborates with schools, and offers ceramics workshops and classes on ceramic culture, including Japanese tea ceremonies using Tamba ware.

By hosting events and working closely with the local community, the museum helps revitalize the “Tamba Pottery Old Village” area. A visit to the museum is essential for anyone wanting to understand Tamba ware deeply. The museum houses over 3,000 pieces, showcasing the diverse colors, shapes, and uses of Tamba ware across different periods. While Tamba ware is often associated with simple red clay jars and urns, the permanent exhibition reveals the rich variety of styles and techniques that have evolved over centuries. This exhibition highlights Tamba ware's close ties to everyday life, reflecting changes in lifestyle through the ages and featuring modern pieces that seamlessly integrate into contemporary life.

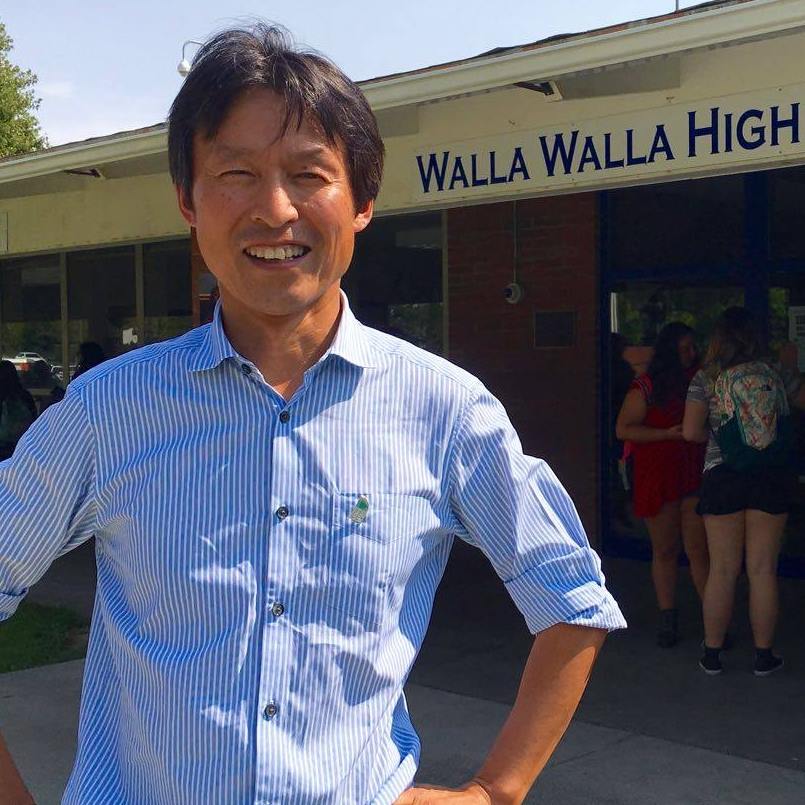

Hideki Doi is the Assistant Director at The Museum of Ceramic Art, Hyogo. He is also the Vice Chair Person at the Sister City Committee between Walla Walla, WA. U.S.A. and Tamba Sasayama, Japan.