MoCA/NY is committed to unearthing ceramic cultural heritage sites to reveal their history, cultural significance, and geological clay characteristics, as well as to elevate the narratives of the artisans who established the region’s reputation and its influence on artists living and working there today.

Mashiko is informally known as the Mecca of Mingei, a term popularized in the 1920s by the Japanese philosopher Soetsu Yanagi, which is an abbreviation of minshūteki kōgei, meaning "folk craft." Despite being a small rural town in Tochigi Prefecture with a population of around 22,000, Mashiko became a popular destination for folk pottery aficionados after Shoji Hamada, leader of the Japanese Folk Crafts Movement, established his ceramics studio there in 1924, drawn by the charms of rural life.

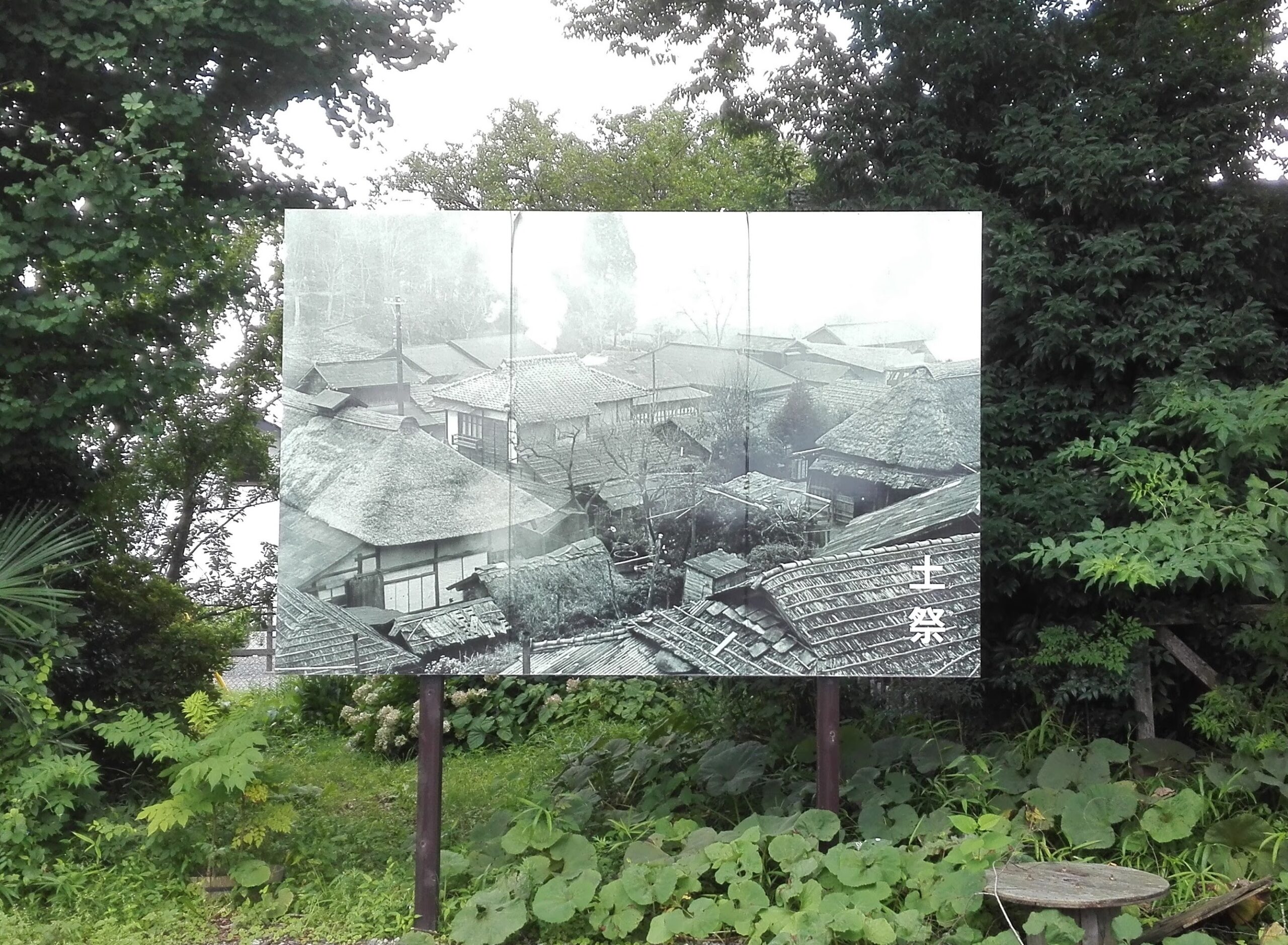

Located about 150 km—or a two-hour drive—from Tokyo, Mashiko’s landscape is dominated by mountains, forests, and farming fields. With a predominantly agriculture-based economy, the region began to flourish as a pottery center only at the end of the Edo period. This shift occurred in 1853, when potter Keizaburo Otsuka from nearby Kasama built a kiln there after discovering high-quality clay. Mashiko clay is known for its richness in iron and silicic acid, which give it its distinctive brown color, rustic and thick body, and high-temperature resistance.

Beginning in 1857, the region's feudal clan started sponsoring Mashiko ceramics, overseeing their distribution by horseback to the banks of the Kinugawa River (in what is now the city of Mooca). From there, the ceramics were transported by boat to Edo (now Tokyo) for sale.

With Japan's modernization and the transfer of the capital from Kyoto to Tokyo during the Meiji period (1868–1912), potters from other regions began moving to Mashiko. This migration coincided with a growing demand for ceramics in the capital, a trend that intensified following the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, which destroyed half of Tokyo. In the next decades, Mashiko became the largest ceramics center in the Kanto region, specializing in the production of household and kitchen utensils such as zakki (misō containers), kame (jars for preserves), kamakko (small disposable lunch boxes), and kishadobin (teapots sold on train station platforms with hot green tea).

Although the decades of recession between the two world wars were challenging for Mashiko potters, the region thrived during the 1950s and especially in the 1970s, during Japan's so-called folk crafts boom.

Thanks to Hamada and the Folk Craft Movement’s proselytizing activities in Japan and internationally, artists, potters, and designers from around the world began coming to Mashiko to learn ceramics. Starting in the mid-1960s, many were taken in and mentored by Hamada’s former apprentice, Tatsuzo Shimaoka, motivated by the spirit of curiosity and adventure emblematic of the countercultural movements of the era.

At the same time, corporate dropouts (known as datsusara in Japanese), that is, white-collar workers who quit their jobs, began moving to the region to pursue pottery, attracted by its slower rural lifestyle. This openness set Mashiko apart from other historical pottery areas in Japan, often known for their insularity.

Rather, it boasts a diverse community that includes individuals from traditional pottery families, both local and from other regions, as well as art university graduates, self-taught artists, foreign migrants, and sojourners seeking hands-on pottery experience. Beyond Mashiko's rich history of pottery production, the region appeals to newcomers with its mild climate, closeness to the capital, and the possibility to sell their work on-site.

One such venue is the Mashiko Pottery Fair, created in 1966 and held twice a year, in fall and spring. Visitors can explore the wide diversity of ceramic styles produced in Mashiko, ranging from traditional Mingei pottery—popularized by Shoji Hamada and characterized by its brown glaze and slipware decoration—to more individual styles that drawn on both Eastern and Western traditions, as Hamada himself did, as well as factory-made ware.

The town also hosts various folk events, such as the Gion Festival, held annually from July 23 to 25. During the festival, locals carry sacred mikoshi (portable shrines) around the streets, perform the lion dance (shishimai), and launch traditional hand-held fireworks (tezutsu hanabi).

At the slope of Mount Tokko, the town hosts Saimyoji, one of the four oldest Buddhist temples in eastern Japan, originally built in 737 and rebuilt in 1492. Visitors to the temple can see a rare statue of a laughing Enma, the Japanese King of Hell, and other exceptional Buddhist figures, such as Datsueba, the Hag of Hell.

With Mashiko pottery designated as a Traditional Craft Product of Japan, the town remains a bolstering center for ceramics manufacture and sales, hosting around 250 workshops and 50 ceramics stores. The main street alone, known as Jonaizaka and located a 15-minute walk from Mashiko Station, features about 30 pottery galleries, shops, and cafes (most of which close between 4 and 5 p.m.).

At the westernmost end of the street, housed in an impressive thatched-roof building, is Higeta, a 200-year-old indigo dyeing studio now managed by its ninth generation. Visitors can observe the dyeing process for cotton—also grown by the family—along with other fibers, as well as yarn spinning and handloom weaving techniques.

At the easternmost end of Jonaizaka stands the Mashiko Cooperative Center, established in 1966 and easily noticeable for the giant statue of a well-endowed Japanese raccoon dog (tanuki), symbolizing prosperity. In a corner store managed by the cooperative, visitors can buy pottery materials and tools, including clay, glazes, and diverse shaped kote (wooden trowels).

From there, it is a 10-minute walk to the Shoji Hamada Memorial Museum, which boasts a collection of ceramics by the renowned potter, as well as works in ceramics, textiles, and prints by other members of the Japanese Folk Crafts Movement. The museum also showcases Hamada’s personal collection of crafts from around the world.

Nominated as a Living National Treasure by the Japanese government in 1955, Hamada established the museum at his home and studio in 1977, one year before his passing, as a space for locals and visitors to witness the richness of folk crafts. As such, the potter’s home, studio, and two noborigama (climbing kilns) are also preserved on site for public viewing.

The walk to the Hamada Memorial will also take visitors past two antique shops: Antique Arts Kyo, which sells mostly kimonos, and Antiques Douguya, offering everything from tableware to furniture, including dozens of old Japanese doors.

Next door to Hamada is Pan de Noemie, a delicious bakery run by a retired couple with a beautiful view of the surrounding farming fields from its second floor. A five-minute walk from there leads to a tiny square with more antique shops and the lovely café and exhibition space Ichitoni Bunnoichi.

Another must-visit for ceramic enthusiasts is the Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art, which opened in 1993 in Jonaizaka. Besides permanent and temporary exhibitions showcasing ceramic works from Mashiko and other artists associated with Shoji Hamada, the museum runs an Artist in Residence program. This program is located next to one of Hamada’s relocated houses and kilns, now preserved on-site.

Visitors eager to try their hand at pottery can book a stay at Minshuku Furuki, a modest guesthouse and hobby pottery school that opened in the 1970s. With 35 pottery wheels available, guests can immerse themselves in the art of pottery-making during their visit.

A four-minute walk from Furuki is Starnet, an art gallery, café, organic market, and sustainable clothing brand founded in 1998 by the late designer Baba Koshi. After traveling the world as a producer for the Tokio Kumagai fashion brand, Baba settled in Mashiko, driven by a vision to create a space that connected local potters and farmers with an urban creative class of artists, designers, and musicians.

Inspired by the modern hippie cafés of San Francisco, Starnet has been responsible for challenging the image of Mashiko as solely a producer of old-fashioned, souvenir-like folk pottery, instead attracting a young, urban audience interested in the intersections of art and nature, satoyama (mountain-village landscapes), and modern urban life.

Overall, Mashiko offers much more than pottery, making it a great place to experience the unwavering creativity and resilience of Japan’s countryside. While traveling by car provides more flexibility, walking (or hiking) allows visitors to get lost in its sometimes bucolic, sometimes decadent landscapes—a scene increasingly common across the Japanese archipelago, where 80% of the terrain is composed of mountains, forests, and small, tenacious human settlements clinging to life.

Liliana Morais, Ph.D., teaches, researches, and writes on craft communities shaped by international migration at Rikkyo University in Tokyo, Japan. She is the author of Cunha Ceramics: 40 years of Noborigama kiln in Brazil (2016, in Portuguese) and academic publications in her field. She is also a contributing writer for Garland Magazine and a board member of the Knowledge House for Craft.

garland mag

knowledge house for craft