The vast and extensive clay quarries in the Westerwald region represent the largest connected deposits in Europe. Only a few other regions in the world are known to have clay sources of comparable size and quality. The Westerwald clay is distinguished by its exceptional ductility, virtually impurity-free composition, and excellent sintering properties. These clays are perfectly suited for stoneware production–a high-fired, waterproof, acid-resistant, impermeable clay.

The rich clay resources, together with abundant timber in the region, earned Westerwald the moniker "Pot Bakers’ Land" or Kannenbäckerland. The proximity of major long-distance trade routes such as the Salt Way and the Rhine, key European arteries, was pivotal in transforming Westerwald and its stoneware into an international success story.

Kilns capable of reaching temperatures up to 1200 °C were documented in the Rhineland as early as the 13th century. The oldest documented evidence of pottery kilns in Höhr dates back to the year 1402.

Extremely poor working conditions, warfare, and penury triggered migration movements across Europe, including the Westerwald region. Around 1600 skilled pottery masters from the Rhineland, Raeren in Belgium, and Lorraine began migrating to the so-called Pot Bakers’ Land (Kannenbäckerland). They infused fresh vitality into local craftsmanship, bringing new forms, decorative motifs, and new glazing and firing techniques. As a result, the pottery trade in the region experienced a major boost in the following centuries.

During this period, the distinctive pottery of the Pot Bakers’ Land developed: a grey, salt-glazed stoneware vessel adorned with cobalt blue painted decorations. The vessel shapes often show a carinated or angular shape achieved by the emphasized articulation of the different body parts through fluting or ridges. Cobalt blue painting was complemented by additional decorative techniques such as stamping and applications.

These vessels were embellished with depictions of prince-electors, bishops, biblical narrative cycles, and very mundane scenes featuring barn dances or mercenaries. Apart from everyday household ware produced for local sale, the potters also worked on commissions that were traded and sold internationally. Westerwald stoneware had become a product on the global market!

In Germany, the Baroque period, a new Italian style that developed after the deprivations of the Thirty Years’ War (1618 – 1648), had a significant impact on pottery. Westerwald experienced an economic upturn, leading to the establishment of new potteries everywhere. In 1771, the guild in the Pot Bakers’ Land (Kannenbäckerland) reached its zenith with six hundred master craftsmen in twenty-three villages. Aside from these, there were many so-called Schnatzer–individuals who, for various reasons– could not or should not be named master. The increasing number of competing potters led to a decline in quality, subsequently causing prices to fall. Faced with this situation, regional authorities were forced to take regulatory measures.

In addition to everyday pottery, craftsmen in the region specialized in creating drinking vessels, figurines, and ornamental pieces. Appliqué as adornment became popular—lozenges, medallions, rosettes, or blossoms were intricately and elaborately crafted and placed. Furthermore, new patterns were introduced, such as hatched lines or impressions made using a wooden stick and stamped decoration.

The products originating from the Kannenbäckerland were renowned for their high quality supra-regionally. Affluent clientele, including the aristocracy, entrusted and commissioned the potters with their specific wishes and needs. This is evident in the personal crests or emblems, such as "GR" for George Rex (King George of England).

From the 18th century onwards, traditional stoneware products faced stiff competition from European porcelain and modern stoneware, gradually losing favor among solvent customers. Out of necessity, the potters focused on producing greyish-blue everyday household tableware up to the middle of the 19th century.

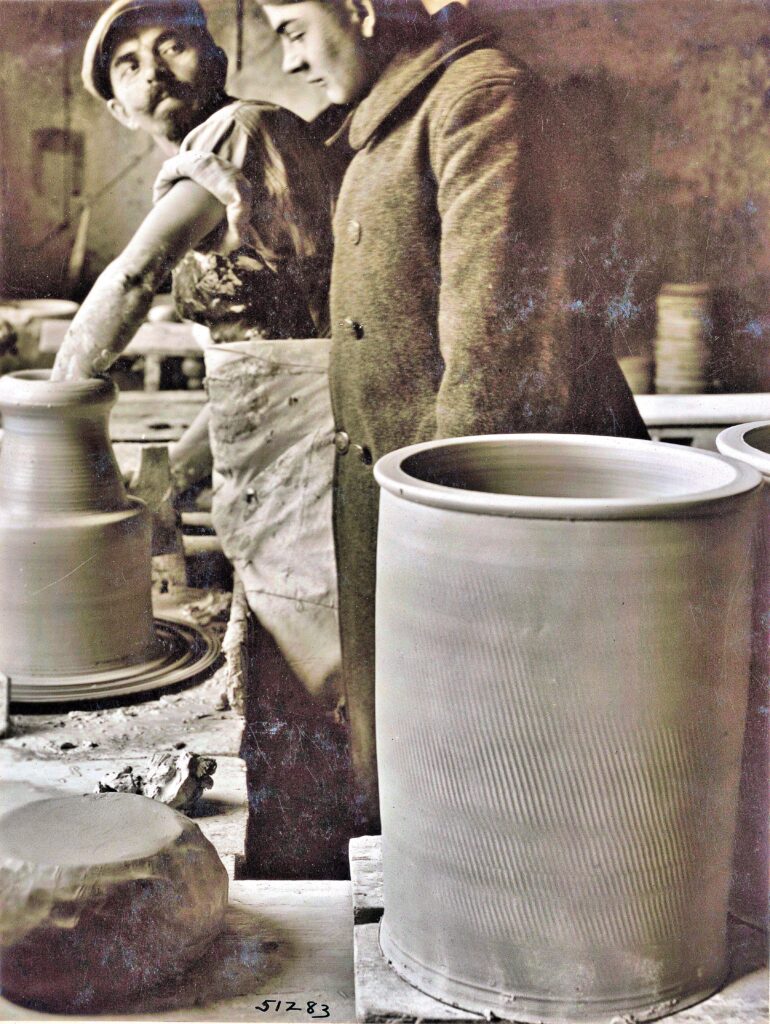

A turning point occurred in 1864 with the recruitment of Bohemian modeler Reinhold Hanke. The long-desired technical and artistic change finally began as Hanke applied his skills to the hitherto traditional stoneware production, collaborating with

Peter Dümler, a talented designer in his company. By 1872, they developed a plaster vessel mold for repeated use, accommodating a thrown clay barrel. This new method enabled Hanke to create intricate, custom-made objects. Honored at world fairs and the recipient of numerous international awards, Hanke is seen as a legitimate heir to the long-standing Rhenish stoneware potters.

Progress now took its course. Driven by factory owners Friedrich Wilhelm Merkelbach II and Georg Peter Wick, improvements in industrialized production increased significantly. This marked a transformative era where traditional German stoneware could now be efficiently mass-produced.

Moreover, the educational reforms initiated by the Prussian government led to the establishment of three major technical colleges devoted solely to ceramics: in Landshut, Bavaria (1873); in Höhr–Grenzhausen (1879); and the former Silesian Bunzlau, now Bolesławiec in Poland (1897). The potter's craft transitioned from being solely passed down through hands-on apprenticeships to becoming a subject of scientific research and analysis, reflecting a broader spectrum of knowledge and skills beyond traditional workshop teachings.

During the increasing industrialization, an artistic counter-movement arose all over Europe at the turn of the 20th century, striving for a renewed strengthening of individualized craftsmanship.

To prevent the region's stoneware manufacturers from missing the boat, internationally renowned artists and designers were engaged. In 1901, Henry van de Velde (1863-1957) arrived in Westerwald, sparking a radical shift in stylistic approach. Simultaneously, Peter Behrens (1868-1940) contributed style drafts and templates, infusing the traditional greyish-blue appearance of Westerwald stoneware with a contemporary design.

Certain factory owners, including Simon Peter Gerz I, Merkelbach & Wick, and Reinhold Merkelbach, took an active role and established successful connections with renowned artists like Richard Riemerschmid (1868-1957). This collaboration ushered in a period of artistic renewal and innovation within the Westerwald stoneware industry.

To ensure their survival, the majority of companies continued manufacturing conventional household stoneware. Products embodying the Art Nouveau spirit appeared overly ornate for the average customer, leading to limited success for these new ceramic offerings. Only a select few companies achieved success with these new ceramic products.

After a reduction in output during World War II, pottery factories gradually returned to pre-war levels of activity in the 1950s, with a primary focus on the mass production of tableware. The Westerwald potteries emerged as the main designers and producers of the Fifties, experiencing a flourishing business that led to the creation of numerous new jobs. For instance, the Jasba company saw a sixfold increase in its workforce between 1948 and 1955.

Immigrant workers from Italy and Turkey also found employment in the concentrated pottery industry, centered mainly around the town of Ransbach-Baumbach. This economic miracle in the stoneware industry ushered in an era of prosperity for the Westerwald region, which endured until the 1990s.

In contrast to other fields of fine art, the evolution of ceramic arts unfolded gradually and without sharp stylistic incongruities. This continuity was partly because handicrafts were not condemned as degenerate art by the Nazi regime; instead, they were supported for their perceived (Germanic) folksiness.

Potters such as August Hanke (1875-1938) and Elfriede Balzar-Kopp (1904-1983) received high acclaim in national and international competitions for their traditional craftsmanship.

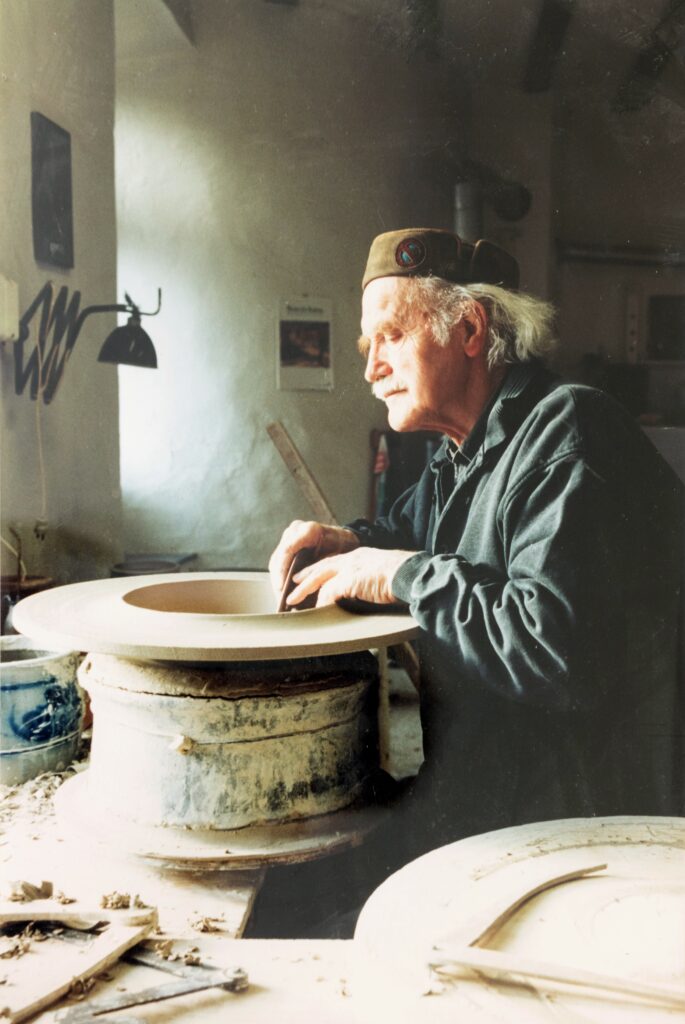

In the post-war period, Westerwald potteries survived by producing crockery in the style of the Thirties. As economic conditions improved, potters began to experiment once again, seeking more individualized forms of expression. The ceramic vessel started to free itself from its traditional role as a functional object, evolving into an autonomous art object. Creative principles from the fine arts and performing arts, such as assemblage, repetition, rhythm, or deconstruction, were applied to ceramics.

Those working or studying at the State Technical College for Ceramics (Fachschule), the Institute for Ceramic and Glass Arts (IKKG), or those active in the many workshops of the region share a common curiosity about what ceramic and glass materials can convey and how to express the art form.

But, the long history of Westerwald stoneware also calls for reflection: What does this place and region mean to us? How does our ceramic culture relate to neighboring regions or other cultures? Many artists employ century-old pottery techniques like wheel throwing or salt glazing to create new and contemporary objects. Every two years, students carry out a firing in the last functioning traditional salt kiln. By immersing themselves in this historical continuum, the region remains vibrant and well-prepared for its artistic future. The narrative of Westerwald pottery continues!

Nele van Wieringen has been the Director of the Keramikmuseum Westerwald since 2018. She completed her master's degree at Koblenz University, Institute for Ceramic and Glass Arts in Höhr-Grenzhausen. There, she earned her doctorate in collaboration with the University of Art and Design Linz with a thesis on the art-theoretical conception of color in ceramics.